Building Global Power to End the Plastic Crisis — And Win a Just Future

Earlier this month, the seventh session of the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-7) concluded. UNEA-7 was an opportunity to advance sustainable resolutions to address the plastic crisis. Instead, many "obstructionist countries deployed the same derailing tactics seen at…the ongoing negotiations for a Plastics Treaty." Plastic Treaty Negotiations have been ongoing since 2022, and PSR-LA has attended five of the six sessions. Below, Maro Kakoussian, Director of Climate & Health Programs, shares more about our journey advocating for health and climate at the international level and the importance of building global solidarity in combating the toxic plastic lifecycle.

Large, compressed blocks of sorted recyclables (like plastic bottles, containers, or rigid items) bound tightly for handling.

Plastic creates profound harm to the climate, the environment, and public health throughout its entire lifecycle—from the extraction and refining of oil and gas and the cracking of petrochemicals, all the way through to manufacturing, consumption, and disposal.

More than ninety percent of plastics are made from fossil fuels, and the plastics sector is now one of the fastest-growing sources of carbon pollution. Communities living near extraction sites, refineries, and petrochemical clusters experience elevated rates of asthma, cancer, reproductive harm, and chronic respiratory disease. These adverse health and environmental impacts cross borders, oceans, and continents. They are not contained by the city limits of Los Angeles, the fencelines of Louisiana, or the townships across the Global South.

Plastic pollution is not merely a waste management challenge. It is a climate justice and public health crisis that originates far upstream, long before a plastic product is discarded and ultimately sent to a landfill, burned in an incinerator, or released into the environment. At PSR-LA, we understand that plastics are not a neutral convenience; plastics, and the toxic chemicals used to make products, are a growing crisis, a climate driver, and a deepening source of environmental racism. The climate and plastics issues cannot be separated—both are products of a fossil fuel system that extracts, refines, produces, and disposes of toxic products while externalizing the public health impacts and environmental harms onto frontline communities.

This is why PSR-LA has engaged in global advocacy — local fights cannot be separated from global structures of power and corporate influence. Transformative policy and community-led solutions require a holistic, life-cycle approach, as well as community organizing, coalition-building, and impactful advocacy to hold global corporations responsible for these crises accountable.

The same industry that drills for oil in Los Angeles neighborhoods and refines petrochemicals in the Gulf South is driving the rapid global expansion of plastics production. Building solidarity with frontline communities from the Global South, Indigenous peoples, and wastepickers is essential for advancing solutions rooted in environmental and climate justice, and guided by the shared lived experience of communities and workers around the world. Whether in Los Angeles, across the United States, or throughout the Global South, communities along the fossil fuel to plastics chain share a common struggle to breathe clean air, and a shared vision for a healthier future where all people can live in safe and thriving communities, reuse and refill systems are scaled, and safer, healthier alternatives are widely available.

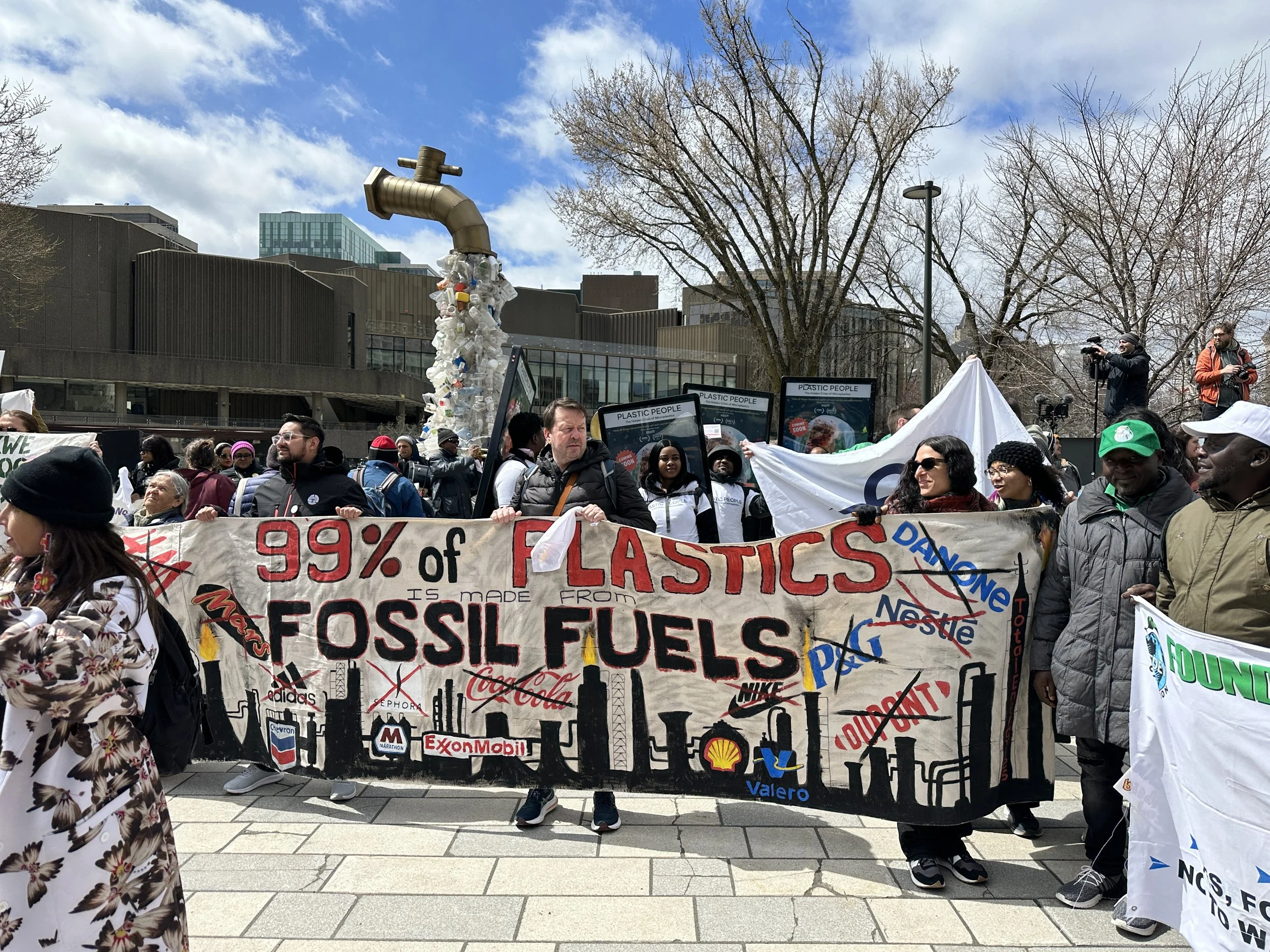

‘Marching to End the Plastic Era’: A show of unity during INC-4 in Ottawa

Addressing Plastics in the International Arena

Despite a strong scientific consensus that limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius is necessary to avoid the most severe climate impacts, current trajectories indicate the world is likely to exceed this threshold. While governments have accelerated investments in renewable energy, electrification, building decarbonization, and energy efficiency, fossil fuel companies have increasingly turned to plastics as their lifeline, promoting false solutions such as chemical recycling to justify continued extraction and production.

At COP 27, I met Robert Bullard, widely known as the father of the Environmental Justice movement, at the first Climate Justice Pavilion.

We witnessed this firsthand in 2022, during the UN Climate Conference (COP) 27 in Sharm el-Sheik, Egypt, the annual conference convened by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). More than 30,000 people attended the COP that year. Still, fossil fuel companies and petrostates sent over 700 delegates, outnumbering civil society and tilting negotiations away from meaningful climate action. Pavilions were dominated by hydrogen projects, nuclear energy forums, panels on carbon trading schemes, and other market-driven solutions—making the pervasive influence of the fossil fuel industry impossible to ignore.

This pattern is now playing out in the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations. Despite the scale and urgency of the plastics and climate crises, UN multilateral spaces intended to deliver global solutions have increasingly been captured by the very industries driving the harm. Corporate influence has increasingly marginalized community-led and public health-driven solutions grounded in Just Transition principles. This narrows the policy space for approaches that center frontline communities, safeguard public health, and ensure an equitable transition away from fossil fuels toward a regenerative, restorative, and truly circular economy.

The sustained influence of the fossil fuel and petrochemical industry within international policymaking spaces is well documented and increasingly difficult to ignore. At this year’s COP, held in Brazil, governments once again fell short of delivering a clear and binding commitment to phase out fossil fuels, despite mounting scientific evidence and widespread public demand. This failure underscores why the leadership and participation of frontline communities, Indigenous peoples, public health advocates, civil society organizations, and environmental and climate leaders are not merely important but indispensable.

As negotiations toward a Global Plastics Treaty (GPT) advance, these actors play a critical role in counterbalancing corporate influence and reorienting the process toward civil society and the interests of frontline communities. Unlike the climate negotiations, the plastics treaty still presents a meaningful opportunity to pursue a more ambitious and equitable outcome. While international agreements can help set the ceiling for domestic policy ambition, their broader value lies in convening frontline communities from across the globe to build collective power, exchange strategies, and advance upstream solutions grounded in justice, health, and accountability.

The Global Plastic Treaty Negotiations: Engaging with Frontline Leadership, Climate Justice, and the Full Life Cycle of Plastics

Our engagement in the GPT Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) negotiations underscores the importance of showing up with a strong, environmental justice and public health-led delegation capable of shaping outcomes and holding decision-makers accountable.

In the spring of 2023, I traveled to Paris for the Second Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-2) meeting, marking the beginning of PSR-LA's participation in the GPT process. The treaty mandate, established by UNEA Resolution 5/14 in 2022, called for a legally binding agreement that addresses the full lifecycle of plastics, including their design, production, and disposal. Paris was followed by negotiations in Nairobi (INC-3), Ottawa (INC-4), Busan (INC-5), and Geneva (INC-5.2), each reinforcing the high stakes of the process and the deep political barriers to progress.

EJCAP delegation during INC-3, INC-4, and INC-5. Members who joined include staff from PSR-LA, Black Women for Wellness, Paicoma Beautiful, East Yards Communities for Environmental Justice, Just Transition Alliance, and Valley Improvement Projects.

From the opening day in Paris, the influence of fossil fuel lobbyists and major petrostates was evident. Fossil fuel-aligned countries repeatedly used consensus-based decision-making to delay and obstruct progress, echoing tactics long observed in international climate negotiations. The interests of oil, gas, and petrochemical-producing states are closely aligned, with a shared objective of weakening or stalling any global agreement that could constrain the continued expansion of plastics.

As our participation in the GPT continued, with a delegation from the Environmental Justice Communities Against Plastic (EJCAP) coalition, we ensured it was rooted in coalition-building, solidarity, and sustained education and advocacy. Through EJCAP, we have led and partnered with frontline-centered delegations at each INC session, ensuring environmental justice and public health voices are present, visible, and influential. At each session, our primary goal has been to build trust and deepen alignment ahead of the negotiations.

At the ‘Plastics, Policy, & Public Health’ forum in Busan, NGOs, foundations, scientists, and academics discussed the adverse health effects of plastics.

Over the years, our advocacy has taken many forms, including public testimony during US-led stakeholder meetings, coordinated interventions on the UN floor, public demonstrations, and direct dialogue with negotiators and delegates. In Busan, we held a public health and plastics forum to educate non-governmental organizations, foundations, scientists, and academics about the adverse health impacts of the full lifecycle of plastics. Through this work, we have built strong alliances with partners worldwide, from Break Free From Plastic to communities in the Global South whose leadership is essential to a just treaty.

In Ottawa, we helped organize a just transition strategy meeting that brought together environmental justice allies, Indigenous leaders, wastepickers, and labor representatives from around the world, including San Francisco’s Teamsters Waste Division, Society of Native Nations, the International Alliance of Waste Pickers, and Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives. The room included people whose collective work addresses the entire life cycle of the petrochemical and plastics industries, with shared stories echoing one another—describing the same public health harms: toxic air emissions, poisoned water, chemical exposures, and the burden of waste imports from wealthier nations. The Alaska Communities Against Toxics shared how plastics and toxics threaten the Arctic Indigenous Peoples' land, culture, and health. These conversations are essential, as environmental justice and frontline leaders are frequently excluded from formal United Nations processes. By intentionally creating space for coordination and trust-building, we deepen solidarity and elevate solutions already being developed and led within our communities.

A work at the Les Valoristes Cooperative -Montreal, sorting through recyclables

Another example of a community-driven solution emerged during a tour we joined in Montreal with the International Alliance of Waste Pickers. Our delegation visited a bottling facility that operates a materials recovery system that allows consumers to return cans and bottles for a refund, keeping materials in a closed-loop cycle, reducing waste, creating jobs, and supporting a circular economy led by workers rather than corporations. At the same time, other members of our delegation met directly with Senator Merkley to uplift our priorities for a strong treaty rooted in upstream measures and health protections.

Our demands for the GPT center on protecting public health and advancing systemic change. We call for the elimination of hazardous chemicals from plastic products, the establishment of legally binding global targets to reduce fossil fuel extraction and plastic production, and a clear rejection of false solutions such as chemical recycling, incineration, and pyrolysis. Instead, the treaty must prioritize reuse-based systems, safer material alternatives, and a just transition away from fossil fuels and petrochemicals that centers frontline communities.

Holding the Line for Frontline Communities

Observers during INC-3 in Nairobi

Unfortunately, the INC process has seen barriers to progress that are not technical—they are political. To our disappointment, each new draft released by the chair at the end of the INC process has become weaker as petrostates and fossil fuel lobbyists worked to dilute ambition and remove upstream controls. Lobbyists regularly outnumbered civil society, and many even secured seats within national delegations.

In CIEL’s 2025 report, they found that “234 fossil fuel and chemical industry lobbyists” had registered to participate in INC 5.2 Geneva, outnumbering the combined number of delegates from the European Union (EU) and EU nation states in attendance for the negotiations, raising alarms about the influence of fossil fuel and chemical corporations in the talks. ExxonMobil, the largest producer of plastics globally, had brought six lobbyists, and the American Chemistry Council and Dow each brought six as well.

This influence has created a deep conflict of interest that shaped every debate. Still, through persistent education, advocacy, and direct engagement with negotiators, more and more countries began to understand the full life cycle of plastics and the need for upstream production cuts, leading to INC 5.2.

Negotiations were set to conclude at the end of INC 5, but by the end of the session, the chair’s text still included upstream measures, but it remained far too weak to address the scale of harm facing frontline communities. The risk was enormous. A weak treaty could have been finalized, entrenching loopholes, legitimizing false solutions such as chemical recycling, and expanding waste exports to the Global South. For environmental justice groups, the position has always been clear. No treaty is better than a weak treaty, because a weak agreement would lock in decades of harm and strengthen the petrochemical industry's hand at the expense of public health and human rights.

Despite the pressure, political will for real action grew. In Busan, more than 100 countries made it clear that a credible GPT must go beyond voluntary measures and waste management. They called for legally binding provisions that phase out problematic plastics and hazardous chemicals and place limits on plastic production itself, recognizing that cleanup and recycling alone cannot solve a crisis driven by overproduction. These countries argued that without binding global reduction targets, the treaty risks reinforcing the status quo rather than addressing the root causes of plastic pollution.

When we arrived at INC 5.2 in Geneva, the stakes were higher than ever. The influence of industry lobbyists was overwhelming, and the geopolitical context had shifted with the arrival of a new Trump administration. The danger of walking away with a hollow agreement was real.

Frontline communities taking action outside of the plenary room in Geneva

However, through coordinated advocacy, cross-regional solidarity, and sustained coalition building, frontline and civil society actors prevented the worst outcome. Rather than accepting a weakened treaty that would have legitimized false solutions and reinforced patterns of wasteful colonialism, advocates held firm. The INC 5.2 negotiations concluded without an agreement, preserving the possibility of a more ambitious and health-protective treaty and averting the adoption of provisions that could have locked in long-term harm. This outcome is not a failure; it’s the result of collective resistance to inadequate solutions and a refusal to accept symbolic action while communities continue to bear the burden of pollution and exposure.

We saw clearly in the final plenary how essential frontline voices are. The United States and Kuwait attempted to shut down countries from the Global South that were calling for stronger protections. Industry lobbyists stood ready to shape the outcome in their favor. Yet because frontline communities, Indigenous leaders, wastepickers, workers, and environmental justice advocates were present, coordinated, and vocal, the world did not walk away with a treaty designed by polluters. Our presence helped ensure that the negotiations did not sacrifice public health for political convenience.

EJCAP members with ally Juan Carlos Monterrey Gomez, delegate of Panama.

This is why we continue to show up in global spaces. It is why we build coalitions. It is why we insist that frontline leadership remains at the center of international negotiations that will shape policy for decades to come. Whether through site visits, coalition-building, or direct engagement with decision-makers, we use many of the same advocacy strategies we rely on locally in Los Angeles and California. The scale may be global, but the principles remain the same. Real solutions remain grounded in frontline leadership and community power.

Building Power for a Just and Healthy Future

As demand for transportation fuels declines with the growth of electric vehicles and energy efficiency, the fossil fuel industry has made clear its intention to significantly expand plastics production through 2050. Absent intervention, this trajectory would create new sacrifice zones, entrench existing health inequities, and further accelerate climate change. Yet experience shows that when frontline communities are present, when movements organize in multi-sector coalitions, and when advocates share their stories, the boundaries of what is politically possible can shift—showing up matters. It changes the narrative, shifts the balance of power, and protects the future we are fighting for.

Our international work has led us to cross paths with powerful organizers from South America, India, Argentina, Kenya, and beyond, many of whom come to these negotiations as waste pickers, community leaders, and parents determined to secure a healthier, safer future for their families, reflecting the communities in LA who are fighting for protections and the end of neighborhood drilling. Watch as our delegation tours Kibera, Kenya's largest slum, with local wastepickers who are making a change in their community.

Across local, state, and international arenas, leadership from frontline communities and public health experts is essential to advancing solutions that protect communities and reduce environmental and public health harms. Organizing, advocacy, and alliance-building are more important than ever.

Global decisions shape state and local policy in meaningful ways. International climate frameworks such as the Paris Agreement have informed Los Angeles’ long-term climate planning and helped catalyze city and state commitments to deep emissions reductions and clean energy transitions. In parallel, California, responding to both local community impacts and the broader global plastics crisis, has adopted some of the most ambitious plastics reduction policies in the country. These include the Plastic Pollution Prevention and Packaging Producer Responsibility Act (SB 54), which establishes extended producer responsibility and mandates reductions in single-use plastics, as well as a statewide ban on plastic grocery bags set to take effect in 2026.

Local and international organizing matter precisely because these struggles are deeply interconnected. When federal threats and political backlash intensify, power built at the local level becomes even more essential. At the same time, international spaces must not conflate federal positions with the will or interests of the people most directly affected. The U.S. government does not speak for all Americans, nor does it represent the frontline communities bearing the greatest health and environmental burdens. This is why the leadership of health professionals is indispensable.

Public health is a global crisis that requires a global movement grounded in evidence, solidarity, and care. Our work will outlast any single administration because it is rooted in a fundamental belief: that everyone has the right to live, work, and play in a healthy and thriving community, regardless of zip code, race, class, or gender. A future grounded in justice and collective care is possible, and we are actively building it together.

Build Power With PSR-LA.

If these values resonate with you, PSR-LA can be your organizing and political home. By becoming a member of PSR-LA, you join a local and global struggle for equity and justice that centers public health in climate and plastics policy. You become part of a movement that rejects false solutions, uplifts frontline leadership, and fights for a future in which every community has the opportunity to thrive.

Join us. Let us build power together. Let us win.

A message from MaroIn 2015, shortly after graduating from university, I traveled to Guatemala City while conducting research for an environmental justice organization in California’s Inland Empire. Seeking an international perspective on how environmental pollution shapes daily life, I was taken by my host family to the city’s municipal garbage dump, a forty-acre open-air landfill where hundreds of families lived and worked under conditions of extreme poverty. There, I witnessed entire communities sustaining themselves by sorting through mountains of discarded materials searching for plastics and other items they could sell or recycle, clothing their children could wear to school, or household goods they could repair and reuse.

At the time, I lacked the language to fully name what I was observing. What I was seeing was the indispensable labor of waste pickers operating at the frontlines of a global waste economy structured by overproduction, disposability, and profit. It was also an early encounter with the profound health and environmental harms generated across the full life cycle of plastics, borne disproportionately by communities far removed from the centers of consumption and decision-making. Nearly a decade later, I found myself standing in another landfill, this time in the Kibera settlement in Nairobi, Kenya, as part of an international delegation participating in the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations. The conditions I witnessed in Guatemala City were echoed in Nairobi. Across the Global South, frontline communities continue to carry the heaviest burden of a crisis they did not create, revealing the deeply unequal geography of plastic pollution and global waste.